Over the last decade or two, the dearth of people-oriented development has started to diminish. As the interest in occupying traditional cities, villages and towns has increased, so has the reconnection to the value and importance of building our communities for people as the first priority. One important component of this is the recognition of the human scale. Building places for people requires that the designer of a space focus on the scale of a person and how people use and perceive space. Human beings, for the most part, experience interior and exterior space in a similar manner. The average woman is around 5’4” tall and the average man is 5’9”which equates to a typical human view cone of vision originating at roughly 5’ above the ground or floor plane.

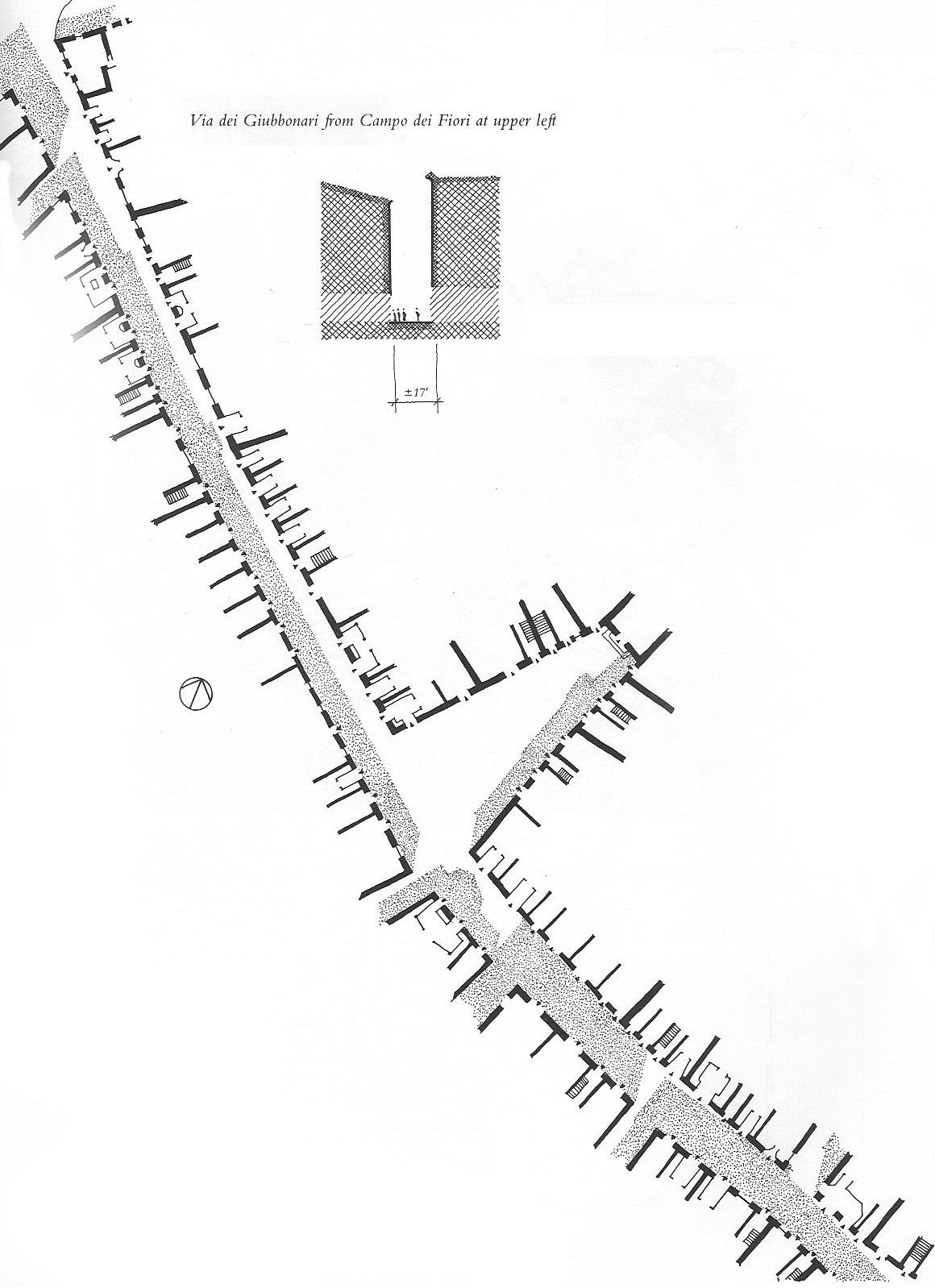

The feeling, whether comfortable or uncomfortable, that an individual gets from occupying and perceiving a space is based on this dimension. In an urban environment, this can best be defined by the width and the height of buildings along the street and the “urban room” that is created by the enclosure of buildings within a space. In the seminal text “Great Streets” by Allan B. Jacobs, numerous examples of successful urban condition are beautifully illustrated to assist in the understanding of how the connection to the human scale is addressed. The development of buildings, structures, infrastructure and the overall built environment should accommodate this humanistic point of reference in order to establish appropriate places for people.

Downtowns, neighborhoods, districts, streets, civic spaces and buildings are the places and elements of the built environment that make up the daily existence of most people lives. The way that a person perceives each of these places is based on our unified view of space and their design should be directly attentive to this human perspective in order to establish successful environments that people want to be within. It becomes quite evident when the design of an environment has not been sensitive to these scale and perception issues. When we use the terms, “places for people” or “placemaking”, the focus on human scale is what is primarily important. When this is done well, a place becomes comfortable to occupy and will be of value to people and municipalities. These are the environments with lasting value and that are worth caring about for decades and centuries.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Mark Nickita, AIA, CNU, APA, BSArch, BArch, MArch is an architect, urbanist, retail entrepreneur, developer, educator and an elected municipal leader. He is the President of Archive DS, architects and urbanists in Detroit and Toronto and co-owner of retail establishments in Downtown Detroit, including the Pure Detroit Stores, the Rowland Cafe and Stella International Cafes. Mark is a City Commissioner and the former Mayor of Birmingham, Michigan.