Toronto, Canada is known as one of the most livable and ethnically diverse cities in the world. It is a city that we have been studying for decades because of its constant evolution.

Toronto is a contemporary example of very effective urbanism. It is a city where the architecture of individual buildings is mostly irrelevant. It’s the urbanism created by the disposition of structures and open spaces that counts. Toronto is a city that is growing in population, due to pro- immigration policies, as well as physically, due to market demands for development.

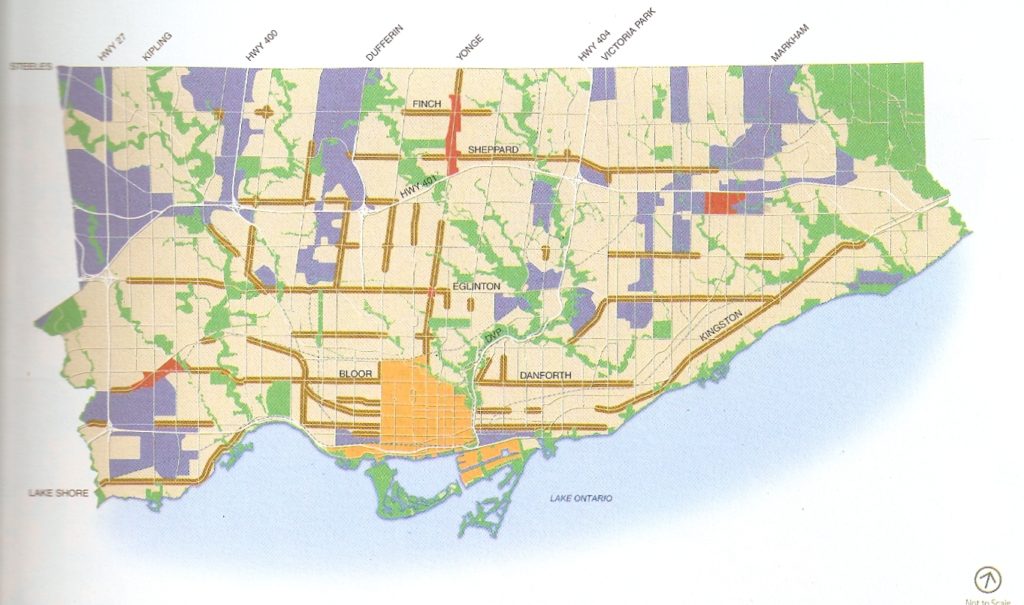

The city is dealing with its demographic and physical growth through certain change agents to create an even more livable city. These moves include:

-Rethinking the relationship between landscape and urbanism

-Rethinking the scale of commercial avenues

-Rethinking the role of tall buildings

Toronto is a city still in transition. It has gone from its “Hog Town” origins of the 1890s- based on the fact that it had become the major supplier of premium bacon to the British Empire-to the distinction as one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world today. Within its metropolitan borders can be seen many of the emerging trends in urban demographics and physical form. Toronto is home to almost every imaginable ethnic group dispersed throughout its greater urban/suburban region.

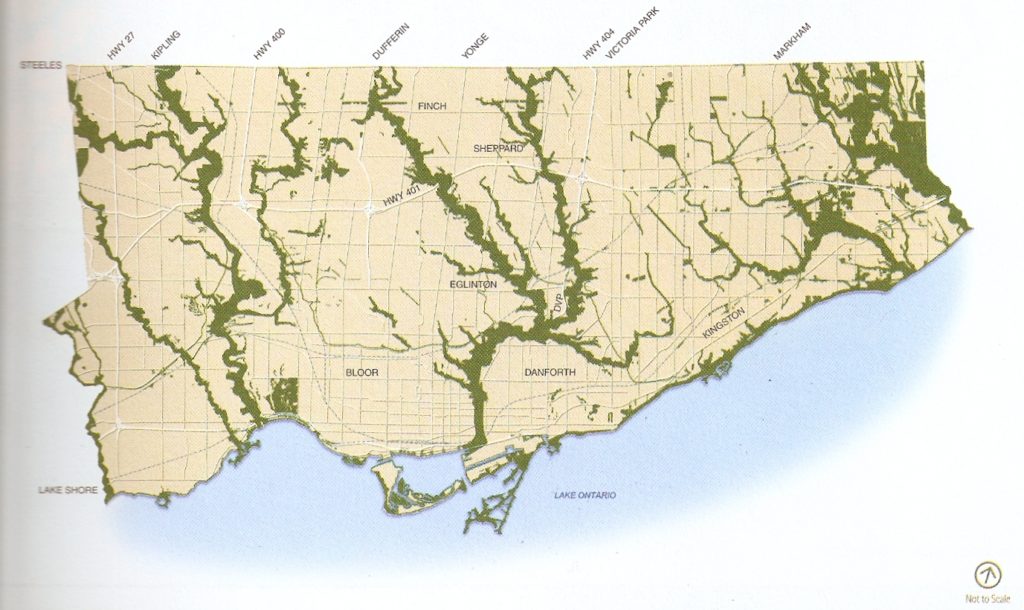

The physical form of the city is an interesting study in urban/nature juxtaposition. One of its most striking and least known physical characteristics is the network of ravines that run through the city. Large swaths of green space, typically about seventy feet in width, snake their way through and beneath the city creating a subversive element within the rigid urban framework of neighborhoods and districts.

Whereas many traditional urban cores have had to manufacture major natural areas within their dense city cores for “relief” (Central Park in New York, the Commons in Boston, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, etc.,..) Toronto has unique natural areas built into its existing fabric. The ravines flow from the edges of lake Ontario through the downtown core and into the inner neighborhoods of the city and beyond. These elements remain essentially hidden due to the fact there are no specifically designated points of entry. They remain a mystery even to long-time residents of the city. They are home to bike trails, soccer fields, and, in a nod to bad planning decisions, partially a freeway. Neighborhoods abut these “green snakes”. Major thoroughfares overlook them. They are a vital part of a unique urban condition. Anomalies in the urban fabric help to alleviate the rigidity of the city grid.

An outgrowth of the emphasis on higher densities is the revaluation of the form and the role of the tall building in the city. The placement, street condition, and location within the city of these new towers are oriented towards enhancing the character of the city.

Dealing with nature as a desirable amenity within the city will be paramount to counteract the rapid suburbanization of North America in the latter half of the 20th century. To ease the now inbred misunderstanding of the virtue of density among North American citizens, natural elements must coexist with, not dominate, the urban realm. Toronto presents a vision for how to achieve this without resorting to the familiar Central Park model.