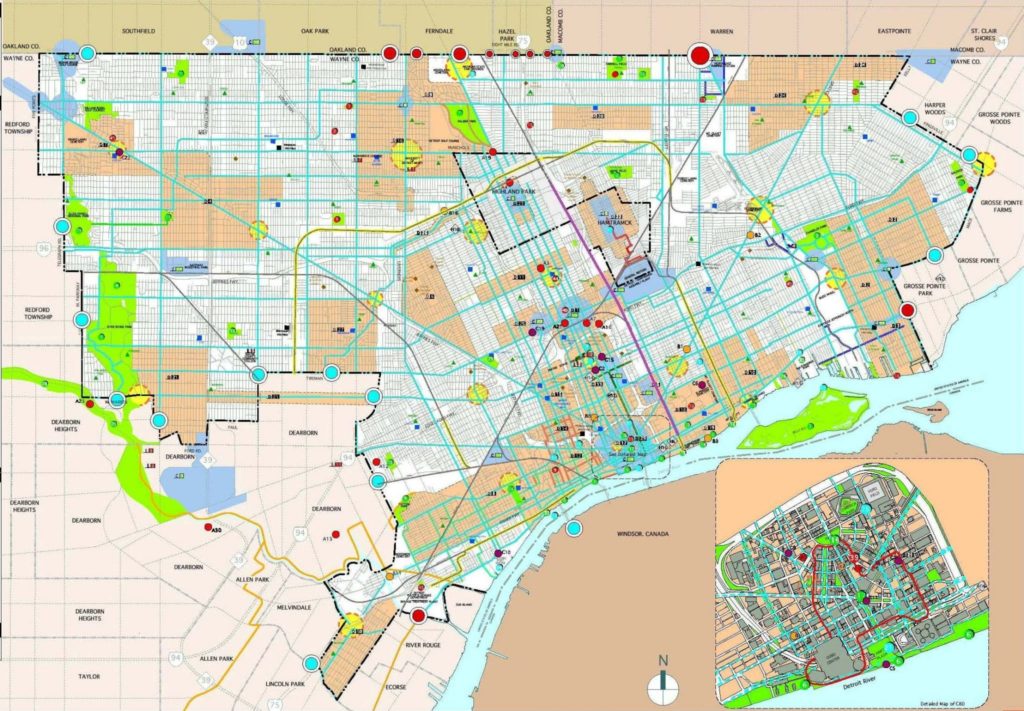

The Non-Motorized plan featuring routes and destinations

In order for our post-industrial cities to restore their past glories they must embrace their existing conditions. Rather than envying what other cities may have they must become Cities of Opportunity.

The City of Opportunity embraces adaptive reuse and rethinking of place and space as a primary “organizing” theme. Urban areas are uniquely equipped to provide this type of experience because of the concentration of the built “infrastructure” of buildings, open space, and landmarks, which create an environment of intense energy. Detroit needs to look at itself in respect to these new realities. Detroit needs to capitalize on its perceived weaknesses as well as its inherent strengths.

Understanding the roles that these elements play will be important in dealing with nature as a desirable amenity within the city will be paramount to counteract the rapid suburbanization of our country in the latter half of the 20th century. To ease the now inbred misunderstanding of the virtue of density among American citizens, natural elements must coexist with, but not dominate, the urban realm.

The Non-Motorized Urban Transportation Masterplan for Detroit is an example of opportunistic thinking in action. We had the good fortune of being one of the urban design consultants for this initiative. It gave us pause in considering what the opportunities for the city really were. When you think of it what better place for this than the city that is known for the auto and yet 30% of its populace doesn’t own one?

DETROIT: THE URBAN CONDITION

The trials and tribulations of Detroit’s past have been well documented:

-population loss to below 1 million after peaking near 2 million in the 1950s

-racial polarization

-economic disinvestment leading to physical devastation

The intrigue of Detroit stems from the fact that it is “shrinking” yet this shrinking is just the thing that is providing it with unparalleled opportunities for [re]development. The urban condition has become much more than the “hole in the donut”. It is a tattered tapestry. The one thing that makes any tapestry, though, is the quality of the connections.

Detroit has (de)veloped into a series of destinations that are disconnected. Currently, “The City” (i.e., government) and designers are searching for ways to link these pieces utilizing unique functions. We can understand how this situation is being reversed by looking at the city in relation to how it is [re]forming itself.

Links between districts need to be developed with visual interest and functions that complement the main destinations. Each node must have a diverse range of options for the visitor to partake of.

These areas are of primary concern. They hold the key to urban restructuring in many post-industrial cities. Detroit is specifically rethinking its core with small-scale entrepreneurial activity as well as grass roots appropriation of public space. This approach fills needs on both ends of the socio-economic spectrum, but it does not only “heal” the city overall. It represents both hope and despair.

TAKING ADVANTAGE OF UNDERUTIZED ROADS AND PARK SYSTEMS

Interestingly, though, Detroit has embarked on an endeavor that can fulfill this goal: a master plan for a Non-Motorized Path System for the entire city. 139 square miles of walking trails, greenways, and bicycle paths that will be used to provide connectivity between the numerous disparate nodes within the city. This plan, once implemented will provide non-car dependant mobility options for citizens of the “Motor City”.

This is crucial in a city where more than half the population depends on public transportation that consists only of buses. I have been fortunate to be one the urban design consultants on this unique initiative5. This initiative takes advantage of the “opportunity” that underutilized streets, parks, districts, and rights-of-way provide. It attempts to stitch together the tattered tapestry.

THE PROCESS FOR THE NON-MOTORIZED PLAN

The Design Team, hired by the City of Detroit, created a planning process that emphasized four key components

a Destination Analysis

b. Route Analysis

c. Infrastructure Inventory

d. Intra-city connectivity

The interesting thing about the infrastructure analysis was that the conclusion was that because of the lack of population concentration within the city, the roads were more than capable of having bike lanes added to them without any disruption to their vehicular capacity.

Once this was determined, the design team combed the city to prioritize the types and locations of suggested routes. The team drove hundreds of miles of roads to verify the suitability of certain roads for non-motorized usage.

The process of realizing the Non-Motorized Path system involved community input at multiple levels. The design team conducted workshops in communities on all sides of the city. The team also worked closely with the Parks and Recreation department and the Department of Streets and Roads. The overwhelming vacancy in the city became a positive for realizing the project. The openness fostered creativity in planning as well as responding to residents needs.

Various community stakeholders were engaged in the development of the criteria for where the path system would go within their communities. The result is a plan that places the amenities where the community feels that it should be, filtered through the experience and expertise of the design team. As a result the goals of the plan are to:

1. Connect users to important sites and districts within the city.

2. Provide Detroit residents with increased options for mobility throughout the city.

3. Assist in the revitalization of the “gateways” to the city (Grand River Avenue, Michigan Avenue, Woodward Avenue, Jefferson Avenue, and Gratiot Avenue)

4. Provide connectivity to other existing and planned regional trail and bikeway systems.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PLAN

Non-motorized plans can have economic as well as community building benefits. Organized walking tours were noted in the final report as a way to bring new visitors into a community. The provision of a defined trail and bikeway provides access to communities. Once people are in a community then they are more likely to patronize local businesses.

The report also noted that a trail and bike lane system tends to promote more interaction among residents, increasing the sense of community. This can not be overstated. Amenities promote a positive feeling about an area from within as well as from the outside.

This excerpt from the final report is probably the most important point to note about non-motorized systems:

Bicycling and walking are generally recognized as excellent forms of physical activity, and can help prevent and or control the chronic conditions that lead to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure to name a few. Those who bicycle and walk frequently generally enjoy better than average health to the point that the United States Surgeon General and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention both encourage such excersise. Health is further benefited by the resulting decrease in fuel emissions that would result from a decrease in vehicle trips….

Older, primarily industrial, North American cities which typically have large areas of urban blight must embrace this concept of creating healthy environments from the decay. Creating accessible environments within the gaping holes in the existing fabric is an area where the City of the Opportunity can make the largest stride towards completely recapturing the spirit of community. A key element in doing this will be a connecting system that embraces, rather than fights, the existing paradigm.

.