Or: How I Learned to Love the One Story Building

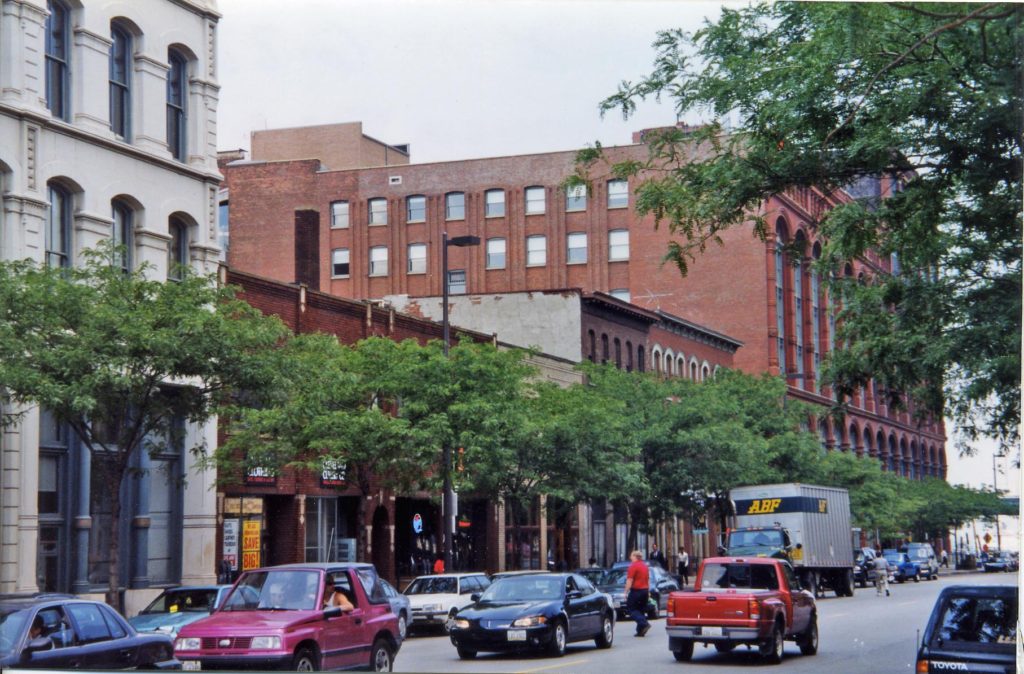

One and two story buildings on streetfront- Cleveland, OH.

One and two story buildings on streetfront- Cleveland, OH.

What to do about our foundering commercial thoroughfares?

As the new economy takes shape and we wonder about the future form of our city, architects and urban designers accustomed to tackling large-scaled, bank-financed, building projects will be faced with repairing the urban environment with smaller structures and adaptive reuse projects. The reality of bank lending will tend to favor single function buildings as safer bets, at least in the short term. The availability of financing will have a profound effect on the shaping of our urban environment.

Traditional commercial thoroughfares (streets such as Gratiot and Michigan Avenues in Detroit) in most midwestern cities were historically 1 to 2 stories. The economics of the recent past made those in the development community accustomed to replacing this building stock with five to six story buildings because of hubris. The market, then breeds sameness. What works for one project is copied ad nauseam. The new economic reality will force us to deal with one and two story buildings because banks will most likely return to very stringent lending practices, requiring only tried and true solutions. Our challenge will be to steer this new development away from city-killing, parking lot oriented buildings. Rather, we should be shepherding in a new area of small scale urban infill fabric and a reexamination of existing facilities.

Will this scale of development work? It has to work.

Once we have come to grips with the question of scale, though, the next question is “What goes in these spaces?”. We need to begin gearing our economy towards focusing creative energy on fostering entrepreneurial efforts. We need to provide opportunities and incentives for the development and prospering of new “industries” in these spaces. Instead of trying to guess what the next hot thing is going to be, we need to provide inexpensive space and allow individuals to use their inherent creativity to generate new ways to prosper. This is the way toward a truly new and innovative city.

In this new economic paradigm the scale of the street will need to be based on these one to two story buildings. This rethinking of the relative value of smaller buildings is already happening along commercial corridors and within older suburban industrial parks. Banal industrial buildings are being re-imagined as hip commercial properties in cities such as Birmingham, Michigan.

The other aspect that must be considered is the role of existing multi-story buildings that line our traditional central business districts. The types of functions that will now inhabit the 1st floor will trend away from pure retail to more service oriented functions such as travel agencies, real estate offices, small lawyer offices, consultancies, aesthetics-oriented businesses, and entrepreneurial activities not yet conceived of. The upper floors may remain vacant; “grey boxed” until the proper tenant direction is determined by the market and the entrepreneurial environment. Philadelphia’s Walnut street is an example of this condition that has existed for many years. This condition exists in most older midwestern and eastern cities; Pittsburgh, Chicago, Baltimore, and Milwaukee are just a few examples.

The Judge Woodward plan for Detroit (1805) has as its most prominent aspect the radial streets that form the major traditional commercial corridors in the region. Today, along these corridors, there are numerous examples of this kind of formerly commercial urban condition. These streets, while being rather wide, ranging from 80 – 100 feet, are lined by one and two story buildings throughout most of their lengths. Still a sense of urbanity exists. The challenge for city builders will be to balance the height to width ratio to create a comfortable environment for people. We must look at the physical profile of the street and begin to make infrastructure proposals that begin to make the scale of the street more pedestrian friendly. These proposals can include street trees, medians, boulevards, and high second or third stories.

Toronto, Canada has embarked on a major initiative to intensify its avenues. While the emphasis is on creating higher density, the current economic conditions warrants a closer look at applicable architectural solutions that do not depend on building height. Major cities such as Toronto, where land value is high, do not have to be concerned as much with this issue because the price to acquire the land necessitates that the scale of development be large.

Districts in Los Angeles are also a source for understanding this new urbanity. L.A., like Detroit, is a car-oriented city. Melrose, Beverly Hills, and many other areas are defined by one and two story streets. These areas are not perfect, but they can provide a basis from which to begin to understand what is truly urban and how large car oriented streets can be accommodated in active areas.

As we move out of this recession towards this new economic and urban reality, we must embrace it not fight it. The scale of the street must respond in two phases. First, a comfortable pedestrian scale must be achieved through the use of infrastructure and attention to the street experience. Secondly, existing buildings should be repurposed so that creative 1st floor activities can flourish in the short term and reuse of upper floors can be accommodated in in the future. New buildings, when and where appropriate, should be set up such that vertical expansion can happen later.

By actively nurturing the unique characteristics of our individual cities and accepting the new realities of the building environment, we can better prepare our urban areas for a successful future.